A Duende post usually begins with a travel destination; a spark of inspiration; and a burning question I need answered. The Architecture for Travellers series is no different. On my trip to Washington D.C. I found myself surrounded by extraordinary architecture, but without a clue how to identify the style or eloquently describe it in the correct vocabulary.

This led me down a rabbit hole of research into the built environment of the United States’ capital, in particular, Neoclassical architecture which is the dominant D.C. style. Of course, there is no understanding Neoclassical architecture without having some foundation in Classical architecture. This is where we’ll start our journey together, as I bring you along for this ride of discovery.

A long, long time ago, in a land far away

Classical architecture can be a broad and brain-scrambling term, a catch-all for a whole bunch of sub-styles that began with the architecture of ancient Greece then was further developed by the Romans.

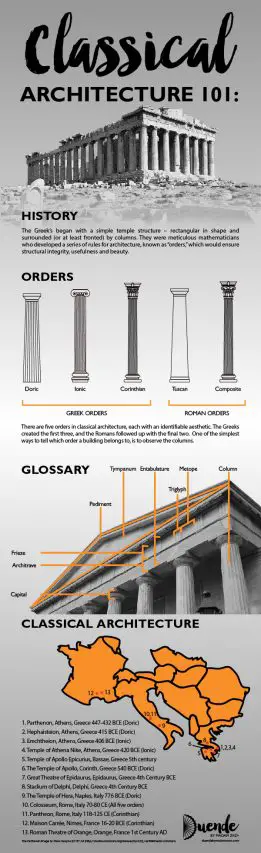

The Greek’s began with a simple temple structure – rectangular in shape and surrounded (or at least fronted) by columns. They were meticulous mathematicians who developed a series of rules for architecture, known as “orders.” These orders would ensure the structural integrity, usefulness and beauty of each building.

Classical characteristics

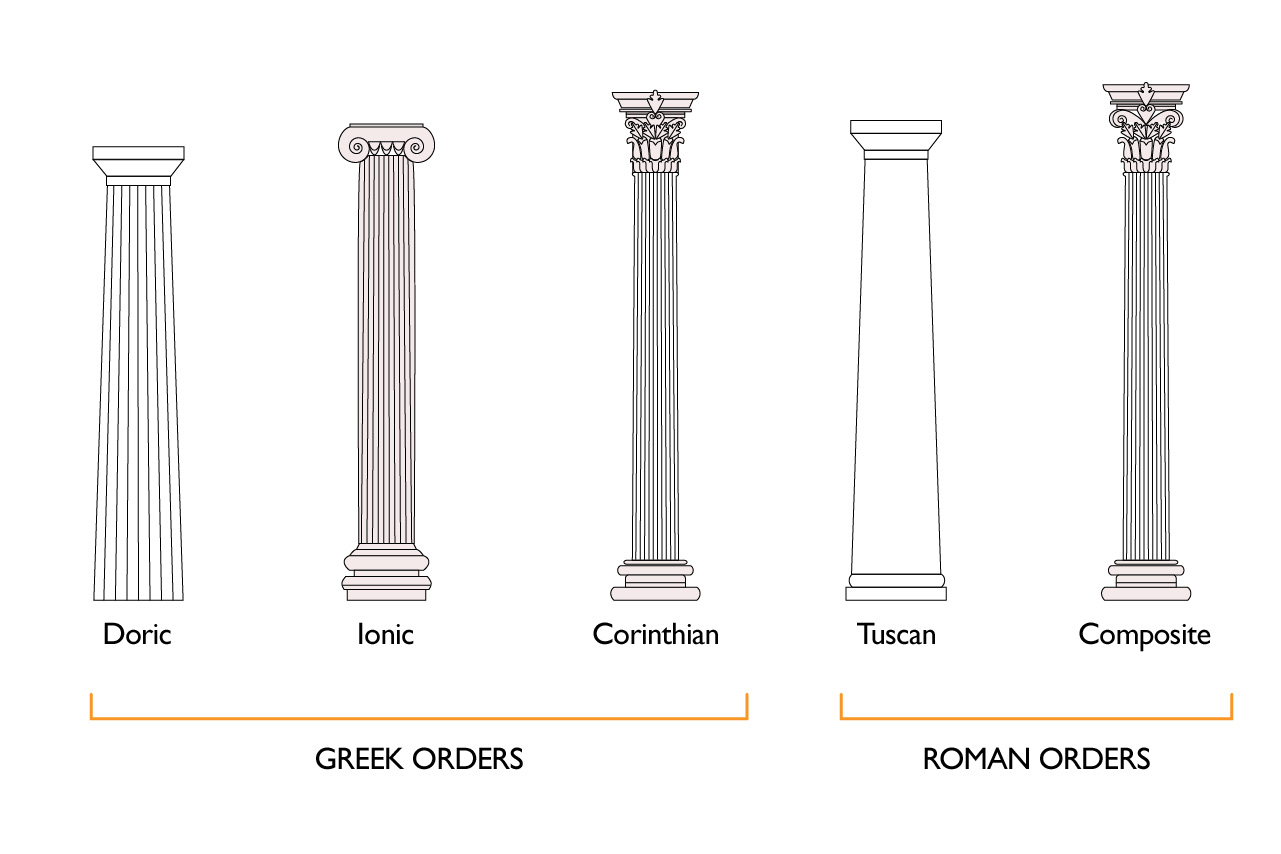

We could go into the complex geometry of Classical architecture, but let’s just bypass the maths and look at the visual characteristics of orders. There are five orders in classical architecture, each with an identifiable aesthetic. The Greeks created the first three: Doric, Ionic and Corinthian and the Romans followed up with the final two: Tuscan and Composite.

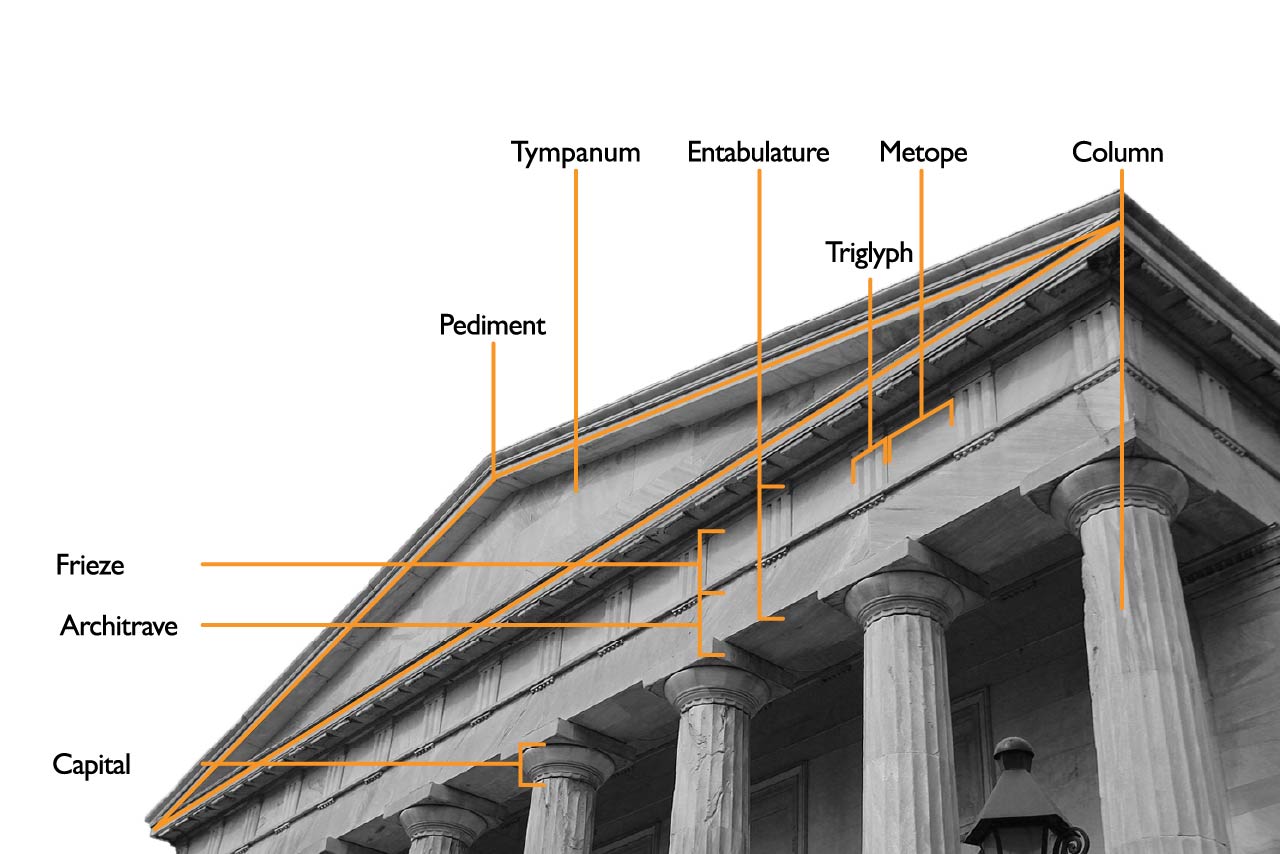

The simplest way to determine which order a building belongs to is to look at the columns and entablature. The entablature refers to the horizontal bands that sit directly on top of the columns, comprised of the architrave, frieze and cornice.

The Greek orders

Doric order columns are the simplest of the Greek orders, which is understandable being they probably were the Greek’s first foray into stone buildings. Doric columns may be smooth or be grooved with 20 shallow flutes. They have no base and a simple capital (the crown-like top of the pillar).

A Doric order entablature generally has a plain architrave, and a frieze decorated with alternating triglyphs and metopes. Triglyphs being the repeated sections with three vertical ridges, and metopes are the square spaces in between triglyphs that are plain or filled with relief sculptures.

Ionic order buildings are more decorative, exhibiting taller, more slender columns topped by capitals embellished with spiral shapes, technically known as volutes, and other motifs. Ionic columns are fluted (usually 24 flutes), possess decorated bases and have entablatures with elaborate friezes.

The Ionic order also makes use of a clever technique called entasis, which is a slight bulge in the columns to counter the optical illusion which makes a straight pillar appear bowed and weak.

Ionic entablatures possess an architrave divided into two or three undecorated horizontal bands. Above the architrave rests a plain or sculpted frieze and a decorated cornice. I’ll delve further into cornice decoration in Part 3.

Corinthian order buildings have columns similar to Ionic pillars, fluted and using entasis, but with far more fanciful capitals, commonly decorated with leaves and floral patterns. The Corinthian entablature is very similar to that of the Ionic order.

The Roman orders

The Romans were happy to adopt the Greek style but needed to put their own stamp on things, so they came up with the Tuscan and Composite orders. As the name suggests, composite is a combination of orders with capitals that incorporate both ionic scrolls and corinthian leaves. The entablature follows the style of Ionic and Corinthian orders.

Tuscan order is the plain-Jane Roman cousin of the doric order. It’s columns are smooth and sit on a simple base, with an unadorned frieze on the entablature.

Still standing

Thankfully due to the pernickety nature of those ancient architects, engineers and builders, not to mention modern archeologists, some of these buildings still stand (with a little assistance here and there). The following is a list of classical architecture that you may like to add to your European travel itinerary or take a virtual tour of via Google Earth:

- Parthenon, Athens, Greece 447-432 BCE (Doric)

- Hephaisteion, Athens, Greece 415 BCE (Doric)

- Erechtheion, Athens, Greece 406 BCE (Ionic)

- Temple of Athena Nike, Athens, Greece 420 BCE (Ionic)

- Temple of Apollo Epicurius, Bassae, Greece 5th century (oldest Corinthian capitals found – first Greek site World Heritage Listed in 1986)

- The Temple of Apollo, Corinth, Greece 540 BCE (Doric)

- Great Theatre of Epidaurus, Epidaurus, Greece 4th Century BCE (Greek Theatre)

- Stadium of Delphi, Delphi, Greece 4th Century BCE (Stadium)

- The Temple of Hera, Naples, Italy 776 BCE (Doric)

- Colosseum, Rome, Italy 70-80 CE (Roman Ampitheatre)

- Pantheon, Rome, Italy 118-125 CE (Corinthian)

- Maison Carrée, Nimes, France 16-20 BCE (Corinthian)

- Roman Theatre of Orange, Orange, France 1st Century AD (Roman Theatre)

If your brain hurts as much as mine does now, let’s regroup for Classical Architecture 101 for Travellers Part 2 – Ancient Structures.

Peace, love and inspiring travel,

Madam ZoZo

3 comments

I am SO insanely into this, can’t wait for the rest of the series!!

Glad you enjoyed it Sandy! Thanks for taking the time to comment and hopefully you’ll love what’s coming up.

Thanks for the details, Zoe.

Had not heard of Tuscan and Composite. It was interesting to be reminded of the differences between Doric, Ionic and Corinthian.

Love your work.

Looking forward to moving onwards and upwards from Architecture 101!